The photographer traveled across Belews Creek in North Carolina to illustrate the ways that pollution industries were affecting small towns across southern America. The resulting book is poetic and subtle, but also disturbing.

Will Warasila’s More Quick then Coal Ash can be described as a book of photos with many layers. On the first look, it may be a simple record of a tiny city situated in Southern America, the numerous faces and places which make up its small community. However, take a more in-depth look and things begin to appear a bit off.

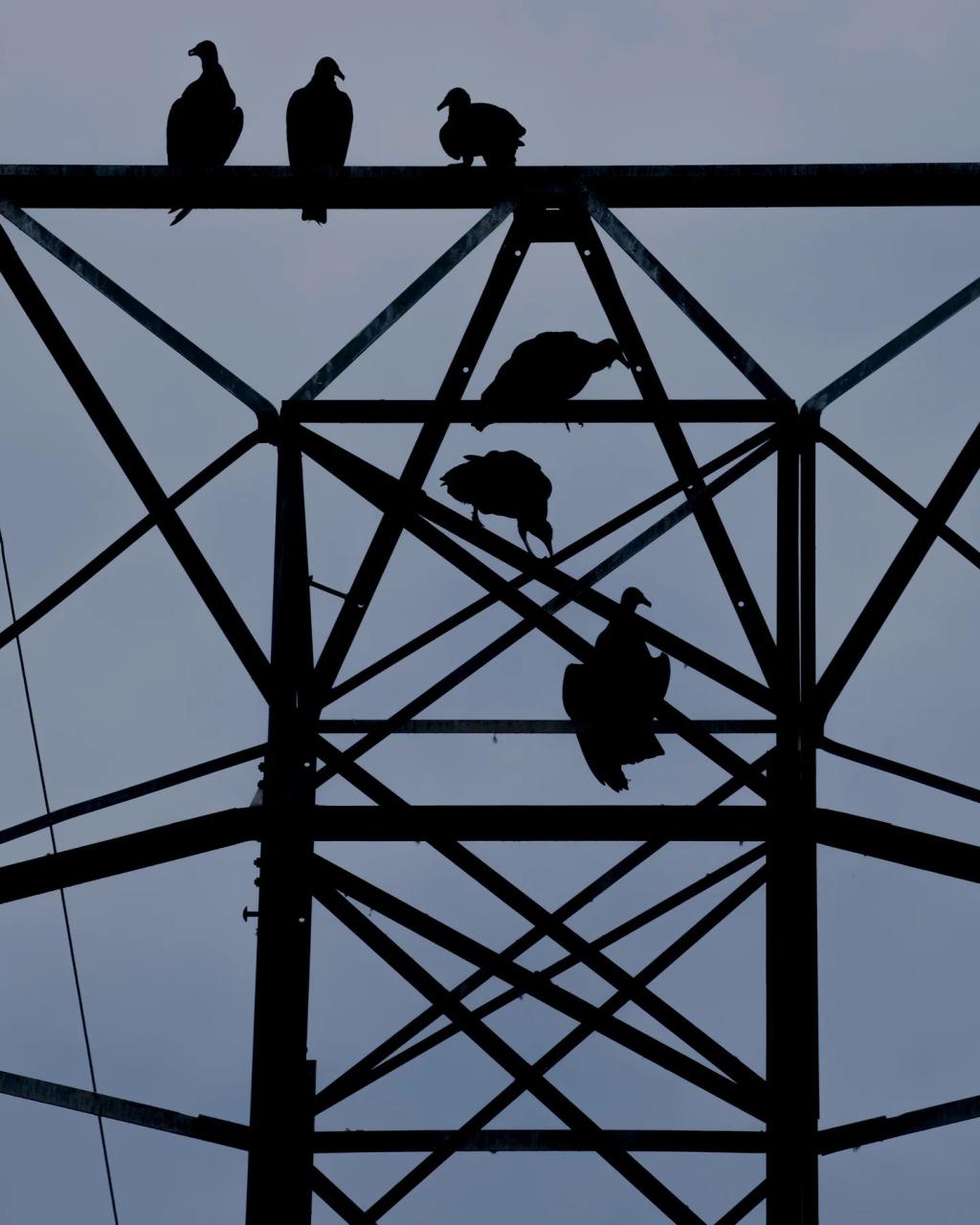

The distance from an idyllic lakeside view the smoke billows appear to be in the distance, while intense, desperate religious events occur repeatedly. The reason is that the images were captured within Belews Creek, a small town located in North Carolina fighting against the pollution caused by its local steam plant. The station is owned through Duke Energy, the station is believed to have resulted in the release of 12 million tons toxic coal ash be stored in a local unlined pond that has caused catastrophic damage to the natural environment of the area as well as the health of the residents.

The project was born from an event that occurred during Will’s journey as a photographer. In his time at the School of Visual Arts, after examining his Magnum lineup, Will decided to move towards documentary photography. he then collaborated with and assisted his with his mentor Geordie Wood, and then moved back to South Carolina to develop his own work. After an “horrific” carbon monoxide spill along the coast of his home state that he started to become concerned about the environmental destruction of communities. Following extensive research relating to connections he’d made on his photography journey, Will was soon directed to Belews Creek.

The title of the book, Quicker than Coal Ash, has its roots in a sermon by an area preacher from Belews Creek, Leslie Bray Brewer. The sermon was delivered during an event to heal coal ash (Will was invited for a month after his first visit to the region) where Leslie requested that the audience “forgive Duke Energy for the damage and the high rates of cancer they caused to communities, as well as combat them in a way that would get rid of all their mess”, Will says. Although not religious, Will recalls this sermon having had a “huge effect” on his. The sermon prompted him to wrestle with issues that would later be the basis of the project, such as “How do you forgive the unsettling actions of a business? What is it living next to the power plant? What is it like to be a victim of the land you live in? How can I capture this community, town or the landscape in a way that is ethical?”

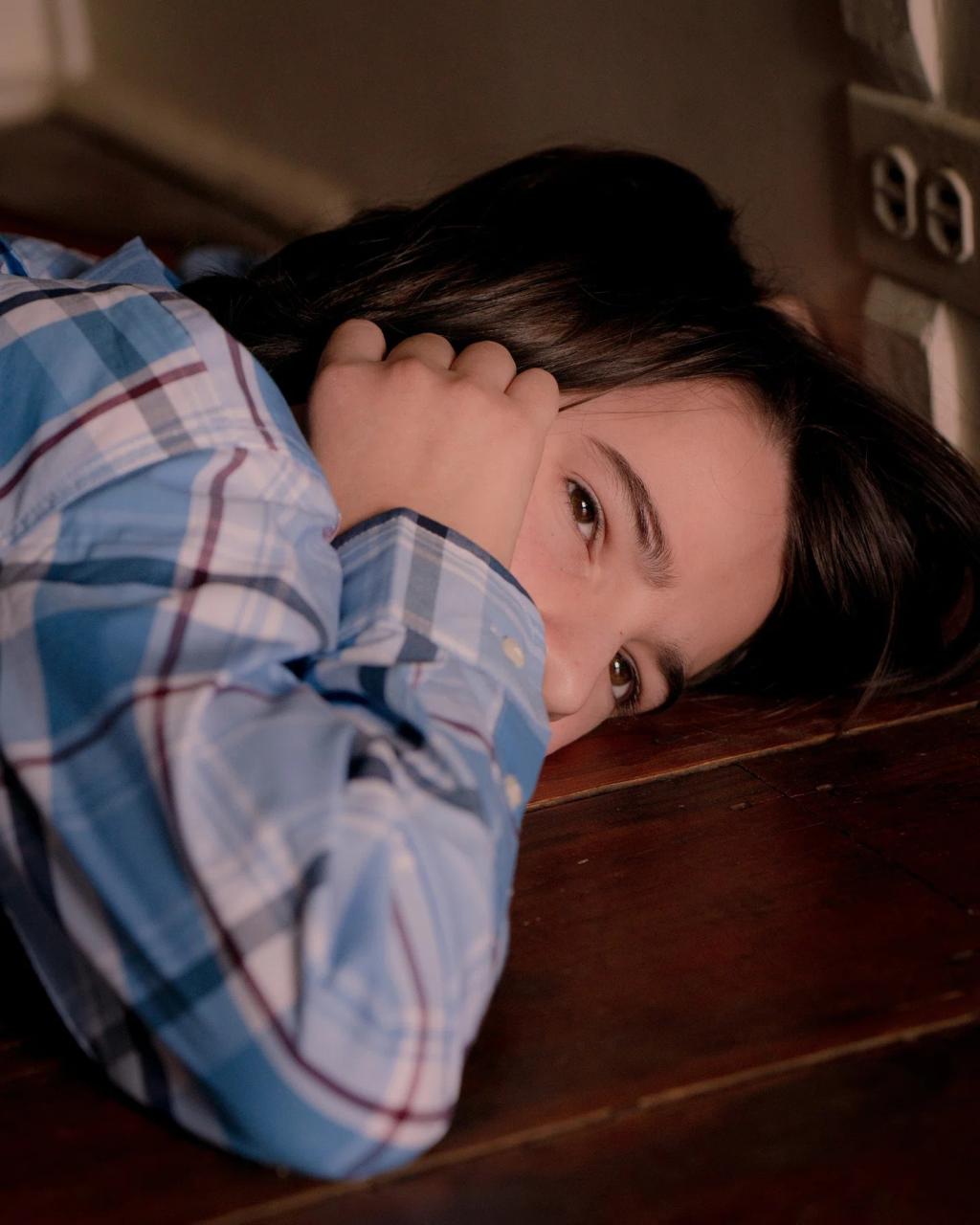

Along with going around town, visiting the Steam Station, taking part in dirt track races, as well as attending the workshops of the non-profit organization The Lilies Project, Will was able to spend a considerable quantity of her day with her Pastor, family, and the church congregation. In actual fact, one of the pictures in the book which remains in the mind of Will was captured inside the home of her family. In the afternoon, she discovered the son of one of them, Malachi and he was sitting with his face pressed against the stairs, in which he heard a stream flowing below. In the picture, the son of Leslie, Malachi is seen lying on his back with his ear in the middle of the staircase, his lower part of his face is blocked by his hands and one finger in his other ear. He has with a distant eye.

In their search for a broken pipe or running water to their dismay they came across nothing. Will continues to elaborate that Malachi was then to return to this place frequently and he began to hear voices from the river. He said that the river was the River from Christ as well as communicating with him. Since the time, Leslie goes to this place every each day to pray for security and health of the town.”

Looking back on the entire project One of the many things Will learned from the project was a greater understanding of how strong and durable the communities of today can. “Often people think of rural America as a one-sided place,” Wills identifies. “That’s not what I saw within Walnut Cove. The differences in race, politics and religion were put aside to achieve a common goal.” Today, Will hopes the book will provide those who read it with the same realization, and a better appreciation of the place they reside – forcing people to consider the source of their energy and how they can organize the local community, and what they can do to combat the many injustices brought on by industries that pollute the environment.

Leave a Reply